South Australian Medical Heritage Society Inc

Website for the Virtual Museum

Home

Coming meetings

Past meetings

About the Society

Main Galleries

Medicine

Surgery

Anaesthesia

X-rays

Hospitals,other organisations

Individuals of note

Small Galleries

Ethnic medicine

- Aboriginal

- Chinese

- Mediterran

The Great Cinchona Robberies

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to Anthony and Robin Radford for their presentation on the production of quinine

in Papua New Guinea.

THE GREAT CINCHONA ROBBERIES:

Philanthropy not theft — the story of quinine production in Papua New Guinea

Robin Radford and Anthony Radford

Adelaide, South Australia

South Australian Medical Heritage Society

February 2014

The almost inappreciable value of the cinchona, commonly called Peruvian bark ... is

universally acknowledged. Hence it becomes a duty to humanity ... to increase the supply

of cinchona trees which yield such valuable barks.

[Memorandum from Dr Forbes Royle to East India House, March 1857.]

By the mid-19th century, quinine was highly valued world-wide for treating malaria. Derived from the cinchona tree, its source and production were jealously guarded in its native habitat by the Andeans of South America.

In time, demand began to exceed supply. Between 1840 and 1870, the South Americans (principally Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Colombia) did what they could to protect their livelihoods. But they failed to stop the Dutch and English from smuggling seed and seedlings to their tropical colonies in South Asia and the East Indies.

They:

- blockaded routes

- threatened the Europeans with amputation

- they salted their seed boxes with arsenic and

- left seed exposed to the sun

The names associated with these robberies were Hasshari, Delondre, Ledger, Weddell, Spruce and Markham.

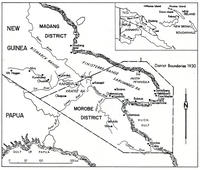

Two of these names had connections with New Guinea: Markham whose name was given to the river and valley which runs down to Lae, and Ledger, who though born in London, later worked and died in Australia, and whose name was given to a species of cinchona, one of those favoured in New Guinea.

Sir Clements Markham, longest serving President of the Royal Geographical Society, made his name on two fronts. Known as 'the father of polar exploration', he also played a lead role in the acquisition and global distribution of cinchona seed and the establishment of British plantations in India. His genius was to present the plot to steal the seeds and plants from under the noses of the nascent Andean republics, not as theft but as philanthropy. The rationale and justification was that by 1850 as many as two million adults a year were estimated to be dying from malaria in India alone, and quinine was the only known remedy.

The global story of cinchona is a saga of myth, intrigue, and 'international skulduggery' with political, economic and geographic tentacles. It pitted Europeans against South Americans, botanists against bureaucrats, and the British against the Dutch, French, and Spanish. In 1842 Royle said that 'with the probable exception of opium (there is no plant) more valuable to man than the quinine yielding cinchonas' - perhaps 'the most interesting plant in botany' and 'the most valuable medicinal plant ever to be found'.

A member of the Rubiaceae family – cinchona is a relative of the coffee plant. Specimens were sent to Carl Linnaeus in Sweden to be included in his new system of classification. He incorrectly spelled the species Cinchona, named after the Condesa de Chinchón.

Cinchona has had numerous synonyms, among them:

- Peruvian Bark

- The Contessa's Powder

- Jesuits' Bark (pulvis Jesuiticus, aka cardinalis)

- 'bitterbark' and the 'bark of barks'

Some of the almost 30 species were identified by colour as having white, grey, yellow or red bark, but the percentage of active alkaloid content varied up to 20 times. Thus its effectiveness as a febrifuge was variable.

Used both as therapeutic and prophylactic, the bitter draft found its way into Indian Tonic Water. It is no wonder that a G & T became de rigeur in tropical climates.

Sir Ronald Ross, the noted malariologist of the nineteenth century, was by no means the first to describe the association of malaria with mosquitoes, as we know from a Vedic bard of the sixth century BC:

The green and stagnant waters lick his feet,

And from their filmy, iridescent scum

Clouds of mosquitoes, gauzy in the heat

Rise with His gifts: Death and Delirium

Susruta text quoted in "Susruta Samhita".

Cinchona also found its way into popular verse. A sailors' refrain in West Africa was

Beware and take care

(quinine wine of the Bight of Benin) -

There's one comes out for [every] forty goes in.'

'A drachm of bark in half a gill of sound wine' was the dose recommended in "Regulations & Instructions: Relating to His Majesty's Service at Sea" by the British Admiralty. Yet the famous German bacteriologist Robert Koch, who cut his tropical medicine teeth in German New Guinea, was initially a sceptic regarding the value of quinine, although he later became an enthusiast.

Mark Honigsbaum[i] has told the cinchona story in his gripping book The Fever Trail. He barely mentions Australia and Papua New Guinea, yet their flirtation with cinchona is worth recounting as a modern postscript to the global story. We propose that the last great cinchona robbery was executed in 1935 by an Australian employed in the Territory of New Guinea.

*************

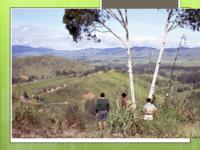

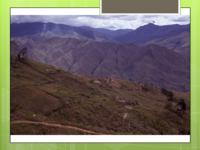

New Guinea was, and still is, one of the most highly endemic malarious countries in the world with prevalence rates over 60% in some areas of the lowlands. The fertile valleys of Highland New Guinea were generally over 5000 feet (1500 metres) above sea level, protected from the malarious Ramu-Markham Valley to the north by the high mountain ramparts of the Kratke Range which formed a barrier had not only daunted foreign penetration but also the anopheles mosquito. [ii] But one followed the other. From the 1930s, highland men were recruited to work on coastal plantations, and then in the 1950s the Highlands Highway provided mechanised as well as human transport into the mountains.

By 1935 the Upper Ramu, today more familiar as Kainantu, was still designated 'uncontrolled' territory. The first patrol post in the Highlands had opened here, and within a few years the area had been fairly thoroughly explored by missionaries and gold prospectors, and patrolled by administration officers. Their reports inspired George Murray, Director of Agriculture in the Mandated Territory of New Guinea, to envisage a Highlands Agricultural Experimental Station at Kainantu where cooler climate crops of village and commercial potential could be trialled and conditions for imported livestock could be tested.

Murray, the son of a Canadian Presbyterian missionary, had spent his early childhood on a small

island of the then New Hebrides, now Vanuatu. He worked in Papua for 17 years before being

appointed Director of Agriculture in New Guinea in 1928.

He proceeded to establish an international reputation. In 1932 it was reported that on return

from his latest "busman's holiday" of twelve months, he had now personally visited every

Department of Agriculture in the tropical world with the exception of those of east and west

Africa.[iii]

In 1935, Murray claimed that 'the major problem of the Administration of all Pacific Territories

is that of checking and, if possible, controlling the mosquito pest' and used his particular

expertise to assist with their public health strategies. But this was only half of the problem.

Quinine was still in common use for malaria, although by 1933 it was challenged by the new drugs

Plasmoquine and Atebrin. Quinine, as well as its bitterness, had serious side-effects if taken

incorrectly. Plasmoquine was introduced combined with quinine but was 'a far from perfect

prophylactic'.

Atebrin had limitations with the side effect of turning skin bright yellow, as well as its

inability to prevent an attack of malaria with the next infected bite. The treatment was

inexpensive, and if taken just before going on furlough, it gave, quote, a 'trouble-free

holiday' for Territorians.[iv]

Quinine continued to be the drug of choice for cerebral and other severe forms of malaria right up until the end of the last century. It would be a huge advantage if it could it be produced in New Guinea.

Like the Andeans before them, the Dutch in Java fiercely guarded their cinchona production, which by the 1930s was 98 per cent of the world's trade. Murray would only be able to obtain cinchona seed by stealth. He succeeded.

The official and unofficial accounts are contradictory or confusing about the origin of the acquired seed, and possibly this was Murray's intention. Publicly, it was claimed that the seed for the original New Guinea plantations came from Amani in Tanganyika, and Burma.

However Murray privately enjoyed telling the story of how a contact in Batavia smuggled a packet of precious seed to him, which he carried home guarded carefully in his coat pocket. George Murray, Director of Agriculture in the Mandated Territory of New Guinea slipped some Cinchona seeds into his pockets while visiting Java in the Dutch East Indies in the early 1930s.

Murray's vision of an 'upland' agricultural research station was now under way. There was still an atmosphere of secrecy and intrigue in the New Guinea Highlands. It was still difficult to access by either foot or plane. Under the guise of experimenting with important commercial plants like coffee or tea, or a local crop like sweet potato, it wasn't difficult to quietly introduce a stolen prize like cinchona. That any overland access to the Upper Ramu would be by way of the Markham Valley was a connection to the cinchona hero which would no doubt have appealed to him immensely.

Fortune favoured Murray when in February 1936, Bill Brechin arrived. He came from a Yorke Peninsula farming family and was a graduate of Roseworthy Agricultural College, South Australia. He was a young man who 'loved life' and whose enthusiasm and youth appealed to Murray. Within three months Brechin was on his way to the Upper Ramu, with six packets of seed in his pocket. He was to be the midwife and nurturer of a most significant component of development in Papua New Guinea.

His first task was to set up nurseries for cinchona and tea seeds in a temporary plot at Kainantu. Next he had to locate a suitable site for a permanent research station. He selected land at Aiyura, a valley across a low saddle less than ten miles from the patrol post, and began to clear it in preparation for planting the new seedlings in September.

Brechin's Aiyura Station reports recorded progress. By September 1937, 10,000 cinchona seedlings were growing vigorously. In March of the following year the seed had produced over 7000 seedlings for planting out.[v] The cinchona experiment was working well: Murray liked to visit for a week at a time.

With the outbreak of World War Two, and the subsequent involvement of Japan, the need for commercial production of quinine became critically urgent. Japan's occupation of Java completely cut off quinine exports to the allied world, just when it was vitally needed for the Forces.

In June 1941 Brechin sent off the first consignment of 250 lbs of wet succirubra bark to Melbourne for analysis.

Tragically in 1940/41 drought struck the Highlands and 50 per cent of the cinchona seedlings died, just as Parke Davis placed an order for 5 cwt of bark. Then further disaster. In January 1942, with other administration officers and civilians in Rabaul, Murray became a prisoner of war. He is presumed to have died with over 1000 others when the Montevideo Maru was sunk off the coast of the Philippines. He would not have known that Brechin had died a fortnight earlier in a plane crash near Kainantu.[vi]

Fortunately the vision and expertise of Murray and Brechin were not destroyed by these accidents of war. Lieut. J. B. McAdam, who previously had had some input into the Aiyura work, was posted to Aiyura and his report emphasised its valuable cinchona plantings, and the importance of Australia having independent sources of quinine 'in any future emergency'.[vii]

The cinchona trees were now twelve feet tall, had flowered and produced the first substantial seed fall. McAdam established 250,000 plants in germinators. He believed that a quinine plantation of 1000-1500 acres was possible. In February 1943, he shipped 200 lbs of bark to Australia. His only concern was the Japanese advance. In fact, not long afterwards, the Japanese bombed Aiyura and Kainantu with minimal damage, and briefly infiltrated the area - causing more confusion than harm.

McAdam remained optimistic.

The promise of 'Stud' seed of Cinchona by the American Government, the abundant production of our own seed and the large demand for Quinine particularly if the War is protracted renders this by far the most important object.

... [T]he continued new construction [will continue] until a figure of up to 2,000 acres of Quinine plantation is established during the next twelve years.[viii]

In 1944, Aub Schindler took over from McAdam at Aiyura. He later wrote: 'In the evacuation of the Philippines in early 1942, [Lt Col. Fischer] an agricultural aide of General Douglas MacArthur was able to bring five pounds of succirubra seed out to Australia then on to the US.

"It was important in those days as Atebrin Mepacrine was in its infancy and in many quarters it was thought that the Japs would be in occupation of the Dutch East Indies after hostilities ceased and hence quinine should be encouraged in land still under our control". The 'stud' seeds, germinated in Queensland, and the seedlings were flown to Aiyura.[ix]

The efforts to continue the quinine plantation and production in New Guinea seem to have gone unnoticed in the general and medical history of World War Two. (Walker, Dexter.)

Cinchona research remained an important function of the post-war revitalised Aiyura. In its extension work, seed was distributed among villages in the Kainantu area and as far afield as Mt Hagen.[x]

Bark was not harvested again until 1949 'when a preparation, Totaquin, was made from the total alkaloids of the bark'. The extracts were sent to Australia for analysis. In March 1952, Schindler awaited the results 'with great interest' and the conclusions drawn from experiments being carried out.

He told me that one million tablets [quote] "were made and tested on some unsuspecting savages in the Milne Bay area. The cure was found worse than the disease". The future of succirubra plantings and the development of village projects depended on these results.

Schindler had problems keeping up the supply of bark because of the difficulties in sun-drying it in the prolonged wet weather. He tested hot-air drying systems. His first attempt caught fire and burnt itself and the drying shed as well. He ordered metal plate for new trays (October 1952).

In January 1953, the future of Highland cinchona was questioned. The introduction of a 'vigourous [sic], reputedly high alkaloid strain of ledgeriana strengthened the prospects of the cinchona village production scheme' but villagers had to be paid to plant it and it didn't have the same appeal for them as coffee.

Schindler recalled in 1969 that by about the end of 1952 cinchona 'had been fully superseded by alternatives [including coffee and tea] and the extensive plantings at Aiyura were abandoned' except for 'a particularly high-yielding strain of ledgeriana' which was still growing in 1969.

Aiyura was forced to take yet another bitter pill. A million tablets were destroyed in Australia just before a Schweppes representative came to 'prospect the scene in New Guinea', as Schindler put it, for obtaining quinine for the bitter part of Bitter Lemon.

PERHAPS MURRAY, AFTER ALL, WAS A PHILANTHROPIST NOT A THIEF.

Footnotes:

- Mark Honigsbaum, The Fever Trail: in search of the cure for malaria. Picador, 2003.

- Radford, A J, van Leeuwen H, and Christian SH. (1976). Social Aspects of the changing epidemiology of malaria in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 70 (1): 11-23.

- Pacific Islands Monthly, June 1932:42. Hereafter cited as PIM.

- PIM, September 1933:13.

- Aiyura station file held at Aiyura in 1968.

- D. Halliday, op.cit. PIM August 1942:35.

- Aiyura station file.

- McAdam, 'Program of Development – Agricultural Station, Aiyura', In Prime Minister's Department, Territories Branch, Correspondence Files, Multi Number Series, 1928-1956 “…Miscellaneous Production – Chinchona Part One 1940-1944. NAA CRS A518 D813/1/5 Pt1.

- Letter Schindler to R Radford, 1969. See also NAA A5/8 BE 812/1/1.

- File without cover, containing correspondence and reports from Schindler and staff, 1946-1954. In possession of R Radford.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The basis for the second half of this paper was Robin Radford's research on Aiyura, published

in her Highlanders and Foreigners in the Upper Ramu: the Kainantu area 1919-1942,

Melbourne University Press, 1987, pp. 168-173. Particular thanks go to Dulcie Halliday

(formerly Brechin), Aub Schindler and John Black for generous access to their records and

reminiscences.